Professor Satish C. Myneni is a Professor in the Geosciences Department and a part of the Molecular Environmental Geochemistry Group. I had the pleasure of being a student in his class GEO363/CHM331- Environmental Chemistry: Chemistry of the Natural Systems which discussed geochemistry in abundant detail. Earlier this week, I conducted an interview related to his work on the geochemistry of compost and how the S.C.R.A.P. Lab is incorporated into his research.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

Questions:

Q: What are the main questions that your research group is asking about compost and how is the S.C.R.A.P. Lab involved?

A: We are trying to understand the chemical variations that happen during compost formations In other words, as raw materials convert to compost, we are studying how the organic molecule chemistry changes and how the bioavailability of metals like iron, manganese, coppers, zinc, and other key elements change. We also want to make these materials used for specific applications. We were looking into the basic leaf litter and wood chips as feedstocks, and then we thought that it would be really interesting to look into and compare them with how food compost from the S.C.R.A.P. Lab behaves. For example, the leaf compost we get is not very rich in nitrogen whereas the food compost has more nitrogen. Can we mix these things to enhance the rate and improve the quality of composting for specific nutrients? Maybe the one with more nitrogen can be applied to lawns and the one with low nitrogen and high phosphorus can be applied to trees so that you can use leaf and food compost, mix them in different ratios and even add fertilizer to improve the rate of conversion on the compost to make them available for different applications

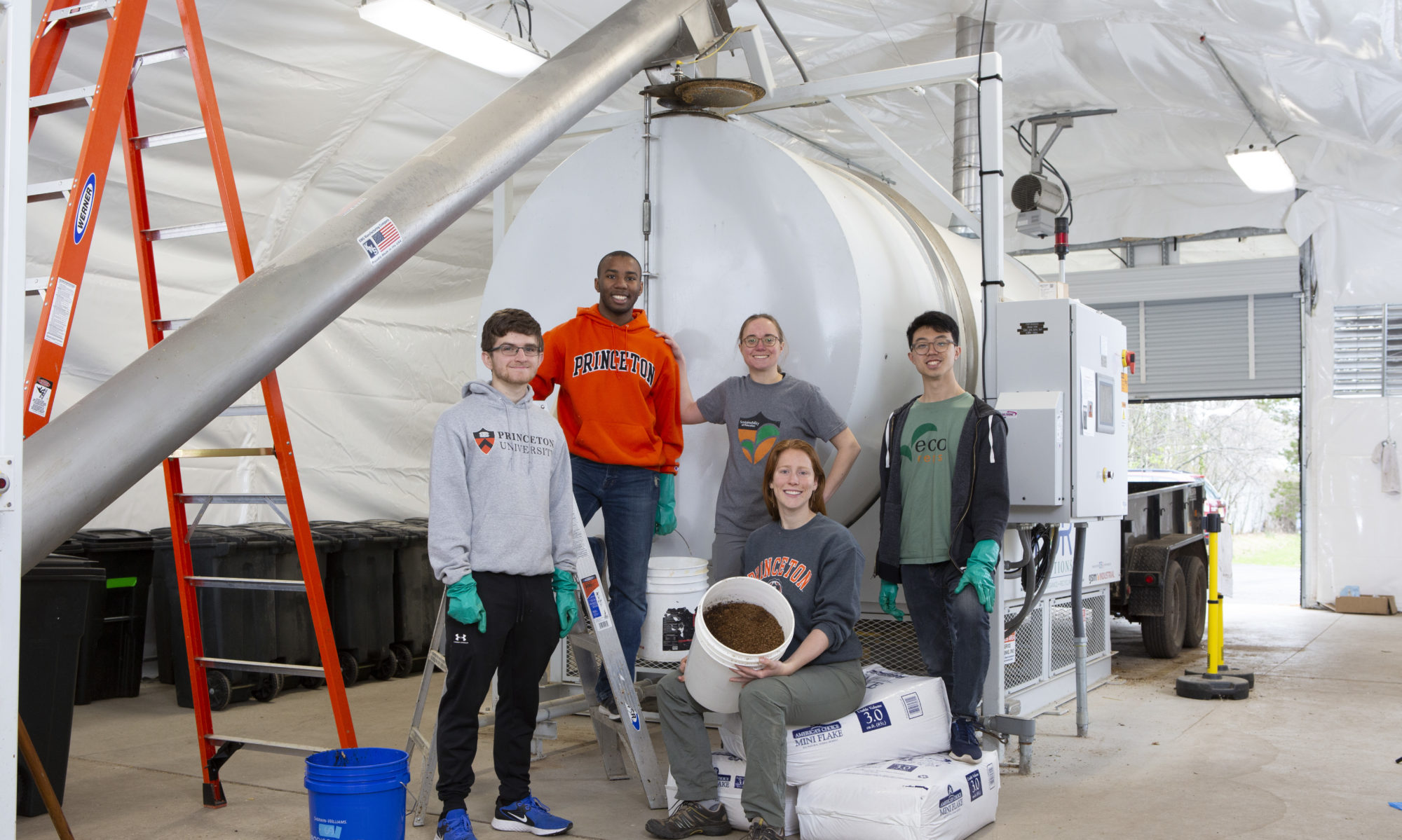

The S.C.R.A.P. Lab is providing food waste that we need for our study. However, it is not pure food waste because it is mixed with a lot of wood which has a big impact on the product. So that is something we have to work out but it is a very good source in getting partly altered food waste from the S.C.R.A.P. Lab.

Q: What are the main research methods your lab is using to answer these questions?

A: We have both field and lab components. In the field, we have different piles: a pure leaf litter pile, leaf litter plus food compost, and leaf litter plus compost plus fertilizer. The fertilizer that we add is coming from commonly-used lawn fertilizers which is mostly urea or nitrogen-based fertilizer. We are adding that to enhance the rate of composting and we do these three different treatments in three different ways. In the last treatment where we add the fertilizers, we add the fertilizers at different ratios (in increasing rates) and also at different times, and we also look at the composting material we get and the leachate material that is produced. These samples from the field form all the different compost piles and we get many samples from these at different time points in the field.

Once we are in the lab then we look at the different organic carbon and metal concentrations and the type of organic carbon that is in both solids and liquids (leachate material). And we are also looking into the bioavailable matter that can be extracted which is going to change with the composting time and the amount of fertilizer we are adding. We use luminescence spectroscopy to look at the types of concentrations of metals and the type of organic carbon that is there. In addition, we use the mass spectrometer and Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in chemistry to get an idea of organic compounds.

Q: What are the main findings so far?

A: Kiley Coates ‘20, who did all of the initial work for her Senior thesis, myself, and some of my graduate students set up the piles and started the experiment in the early part of the year, right before the pandemic. The experiment was going nicely and the temperature in the piles started rising which is what you would expect. And then the pandemic happened and, unfortunately, we could not obtain more samples, so we had to restart the whole project.

Q: Why is this research important?

A: In Princeton (and in other places too) most people believe that fallen leaves are a problem and they just leave them on the street so that the municipality can collect them at different times. This is not only a major hazard for people biking or walking around the streets, but at the beginning of the spring, many people go and buy compost from somewhere else for their lands and gardens. However, they don’t realize that they can compost all of these leaves and use them in their own gardens. We wanted to come up with an alternative method where you are able to convert that big pile of leaves in your backyard into a smaller pile very rapidly with a tenth or a twentieth of the fertilizer that people usually apply. When you do that the compost takes the nitrogen and converts the more labile pool of nitrogen to an organically bound nitrogen form that is much more stable and once it is there in the organic matrix, you can actually apply this ground-up leaf compost to your lawn and slowly release nitrogen. That way, there is no big burden of nitrogen in the surface runoff waters which reduces eutrophication issues while keeping your lawns nice and green.

You can also manage your food waste materials. When you mix them with leaf litter you can get rid of the smell which is one of the things that people complain about compost. The chemicals that give that bad smell are absorbed by the leaf litter, so you can eliminate the bad odor and get all the key nutrients that you need. Overall, I think our research can contribute much more to the reduction of man-made fertilizers, and in turn, nitrogen and phosphorus losses from our lawns.