Happy Friday everyone,

This week’s update is a recap from Intersession week. The S.C.R.A.P. Lab was closed and the composting system remained in its auto-digest cycle while Gina attended the U.S. Composting Council’s (U.S.C.C.)’s Annual Conference, COMPOST 2020, where she presented a case study on the S.C.R.A.P. Lab as part of a panel discussing the composting experience on a large(r) college campus. In between her session, Gina also attended other sessions and participated in a volunteer compost bin making project. Read the highlights below:

PFAS

One of the biggest topics at the conference was a change in the certification standards for compostable serviceware. Starting this year, the Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI) – North America’s leading certifier of compostable products and packaging – will no longer certify compostable serviceware containing intentionally added fluorinated chemicals such as PFAS .

Why does this matter?

PFAS are a group of long-lived chemicals that are used ubiquitously in everyday products for their stain/grease resistant properties. They are found in our clothes, carpets, food packaging, and even Post-It Notes! Because PFAS are water soluble, they enter our waterways and soils, and as a result can accumulate in our bloodstream. In excess amounts, these chemicals may have toxic implications and adverse effects on human health.

What is the impact of the new rule?

About 2,000 or 20% of BPI’s certified products have since lost certification and compostable product vendors are researching and testing new alternatives.

Here at the University, our Campus Dining team will be asking for updated certifications from vendors to limit our procurement of food serviceware and packaging containing PFAS.

Compost Bin Volunteer Project

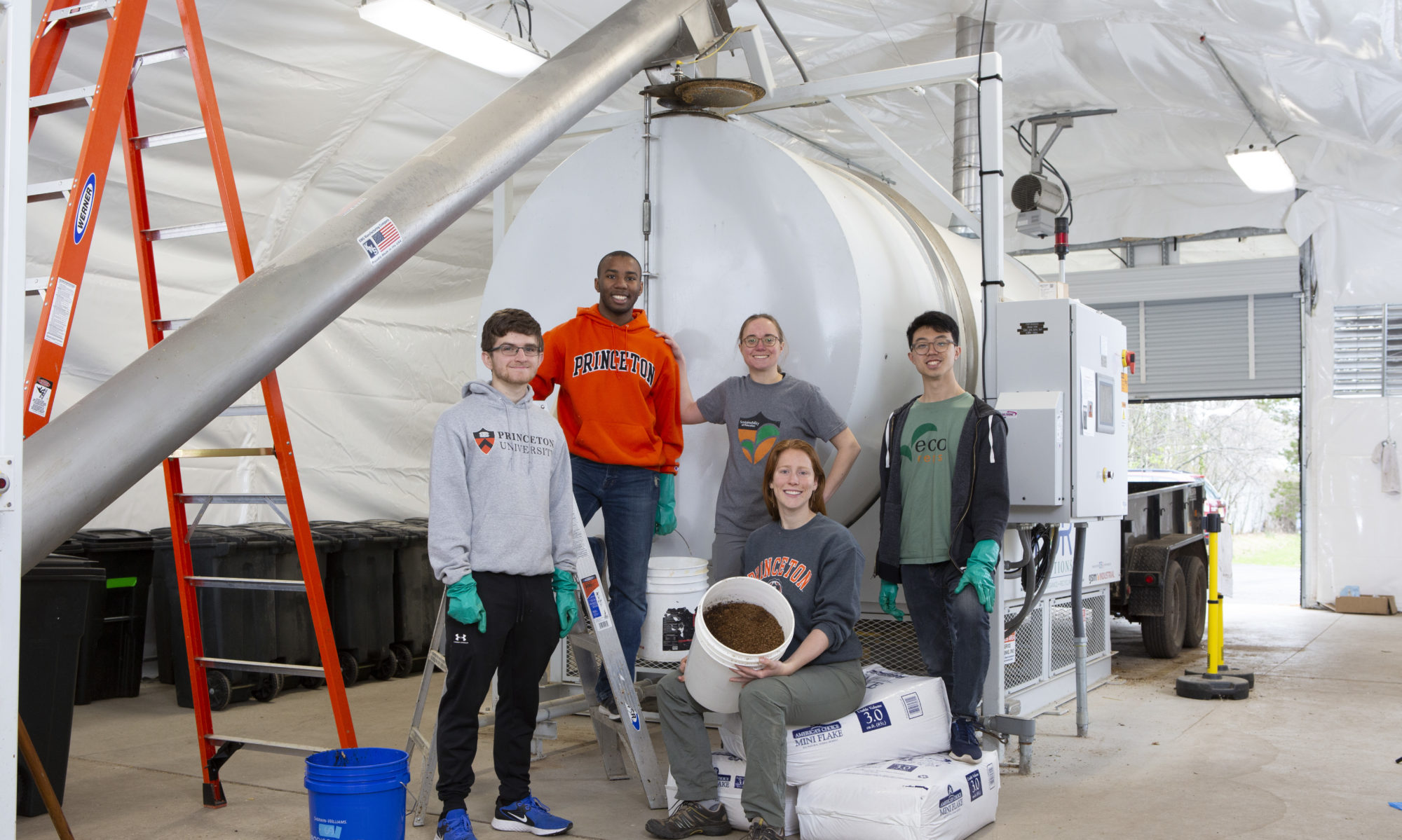

Several other young compost professionals and I participated in a compost bin-making volunteer project with Charleston (SC)’s Green Heart Project – a non-profit that builds garden-based experiential learning projects and school garden programs to educate students, connect people, and cultivate community through growing, eating, and celebrating food.

We built several 8 cubic feet bins and dropped one off at the recipient school in its urban garden as shown below:

Data: End of January

With the S.C.R.A.P. Lab closed last week, this week’s data comes from the week prior and represents the to-date statistics at the close of January.